Cultural diplomacy and heritage preservation: An Interview with Brian Linden

About The Linden Centre:

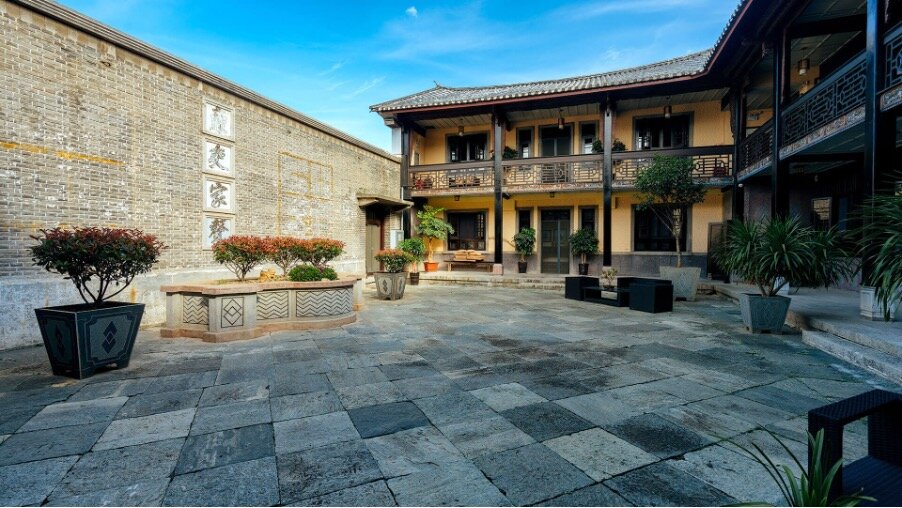

The Linden Centre was founded in 2008 by American couple Brian and Jeanee Linden to direct attention toward the importance of preserving China’s tangible and intangible cultural resources. The Lindens had been residents in China off and on since 1984, and their respect for China’s cultural traditions inspired them to create an alternative hospitality model. Their first site, the nationally protected heritage compound named after its builder Yang Pingxiang, quickly became a beloved destination for guests who wanted more than a newly constructed hotel isolated from its surrounding culture.

For more information, visit: http://www.linden-centre.com

About Brian Linden:

Born and raised in Chicago, Brian began working in Beijing in 1984, playing the leading role in one of the first movies since 1949 to have a foreign leading actor. Brian spent the following two years working for CBS News in Beijing. During that time, he participated in interviews with many Chinese leaders (including Deng Xiaoping). He has completed graduate work at the University of Illinois, Hopkins Nanjing Center, and Stanford University.

Brian's initial career was in international education and investment. He worked in and traveled to over 100 countries before returning to China in 2004 with his wife and two young sons to preserve and repurpose a Chinese nationally protected structure - now known as The Linden Centre. The Centre is Brian's attempt to create a more sustainable model of tourism development and heritage preservation. He now has six sites, each of which focuses on preserving existing historic traditions while incorporating the villagers in planning and managing the final product - a heritage hotel. Their model has been praised by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the US Secretary of State, and hundreds of media and scholars.

In this interview, we discuss with Brian how he became interested in China and what motivated him to set up the Linden Centre. We expand the discussion to talk about China's current cultural diplomatic efforts and how the world perceives China. We conclude our interview by probing into the implications of living and working in China on Brian's identity and having him give advice to young people who hope to contribute to more international cultural exchange.

1. What was your first contact with China?

I first came to China in 1984; I had no idea how much China's culture would impact me. Many foreigners come to China and are immediately overwhelmed by the tangible results of China's 30 years of miraculous growth. While I, too, am proud of China’s recent economic changes, what really attracted me to this country was the connection to the 4,970 years that preceded the most recent thirty years.

It was only eight years after the Cultural Revolution, and there was a desire among many to re-explore China's roots. Some Chinese intellectuals were arguing that China's history was a burden, something that passed on only negative values that limited China’s ability to adapt to the larger world. I was a stranger to this country, and I learned about China through the eyes of the many people who were re-exploring their cultural traditions. It was so fascinating, and I quickly fell in love with this country.

I was surprised to discover that everyone in China embraced me as an equal, or even sometimes special. For somebody who had come from a very humble financial and educational background, the warmth of the Chinese people gave me a lot of confidence.

After spending three years in China, I returned to pursue my Doctoral degree at Stanford. I realized that China had to remain a part of my life. I tried to incorporate it into my profession, which was education investment, but in the 1990s, business opportunities in the Chinese education field were limited. I was working on projects all over South America, Europe, and Southeast Asia, but never in China. I had to make a decision in the middle of my life whether China was going to be a part of my life, or I was going to continue doing what I was doing and come to China for just a vacation every few years.

2. What made you decide to start a business here? What was the process of establishing the Linden Centre?

In 2004, I decided that I missed China too much. I became the person I am now because of my interaction with this country, and I wanted my family to see what I was so proud of. So, seventeen years ago, my wife and I sold our home in the U.S., gave up our jobs, and took all our savings—US$600,000—to China to pursue our dream of developing a rural education retreat.

We wanted to base our retreat in an old building, a structure that could demonstrate the importance of China's tangible heritage. Our mission was to expose others to China's traditional culture.

It’s fairly straightforward to build new. I believe that new construction is taking the easy road in China. Very few businessmen are willing to take on the complications of restoring existing heritage sites. When I see coffee shops and fast food everywhere, I think of the more recent iteration of China. I do not feel a visceral connection with this country’s heralded traditions.

During my extensive international travels, I was disappointed by the outside world’s lack of understanding of China. I wanted to create a platform, physically embodied in our heritage sites, but also intangibly by highlighting the traditions of the local people. We wanted to share our passion for China, using our experiences in this country to share the reality of China with the outside world. The hotel became our social enterprise, allowing us to evolve a sustainable business model while impacting the local communities through our education programming.

3. In the realm of cultural communication and soft power diplomacy, what do you think is the difference between non-profits that seeks to promote cultural communication versus the Linden Centre, a profitable business?

When you run a business, you make decisions in order to survive longer financially. Sometimes your social impact is affected because of the need to remain financially solvent. By demonstrating to the government that we are a functioning business that is not just seeking short-term profits, the government can recognize the social benefits accruing to the locals and more readily supports our efforts. NGOs are often forced to spend more time raising money than affecting social change.

Also, in China, we don't like to “hang our dirty laundry out to the public.” NGOs are often established on the idea of addressing problems in society that government and businesses haven’t addressed. I believe the government recognizes these social challenges and is trying its best to address issues such as poverty alleviation, rural infrastructure investment, education, and health needs. We would like to complement, even in the smallest way, their efforts.

4. Why does the Linden Centre stress integration with local villages and communities? How does the Centre make sure they successfully integrate into the community without exploiting them?

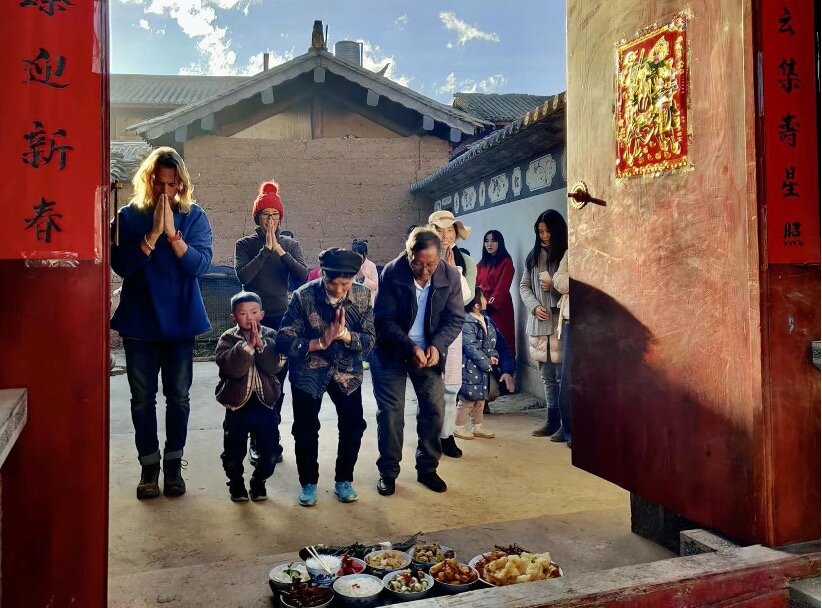

We are attempting to develop a business model that evolves within existing cultural and social traditions, rather than copying models that have been brought in by outside business interests. We aim to let the development happen organically—from within the system. That’s why I want to instill pride in the locals so that they don't just rent out their land and give up. They can share their concerns and aspirations with us, they can participate in our company’s strategic planning and help shape our growth, rather than passively sit back and watch outsiders change their hometown for them.

I believe travel should also include a component of learning, a challenge. We evaluate future sites through a cultural and social lens and not only on how popular they those destinations already are.

5. How do you see the Linden Centre as a manifestation of China's soft power? The Centre also partners with universities in the U.S. and China to promote cultural exchange and support experiential learning. Why do you think this is important?

When the government wants to show China's culture to the outside world, they understandably try to display the best. Many cultural exchanges have been packaged in a way that is a bit too staged, almost a bit too perfect. The Linden Centre attempts to facilitate a more natural interaction between people. Initially, our business was embraced by the adult travel sector. We were able to attract scholars, businessmen, and diplomats, most of whom were affluent and middle-aged.

I, also, wanted to have an impact on young people, facilitating positive experiences with us would alter their lifetime views of China. Our second site was established in 2012 to cater solely to education groups. We first targeted one of the best schools, Sidwell Friends: it's where President Obama's girls, Hillary Clinton's, and many ambassadors’ kids go to in Washington D.C. Our program with Sidwell allowed those kids to come here for four months and immerse themselves in a thriving rural village. We have to give young people from around the world opportunities to understand the richness of this country beyond the cement and neon veneers of Shanghai and Beijing.

6. How do you view China's current cultural diplomatic efforts? Do you think it’s working?

I can understand why political tension is increasing, especially after four years of abrasive remarks from the Trump administration about China. I do hope that people will continue to have patience. China's rise is inevitable. I understand the desire to strike back—nobody wants to be bullied—but I had hoped that China would bide its time and achieve power through its hard work and solidarity.

Additionally, I hope China can present a different way of interacting on the world stage. Confident modesty should be our approach. When we react more aggressively, the West responds in an even more negative way. China should just be patient. Don’t react to the name-calling. I do believe that China is trying so hard to do the right things.

7. As an American who has been working and living in China for quite a while, how do you see your identity under this era of big power politics? How does Western vs. Chinese media frame you? Is there a difference between how media frame your identity and how you think of your own identity?

People treat me with more respect than I deserve. At the same time, China has some institutional challenges that make it difficult for foreigners who truly care about this country to become part of it. After all the years I've spent here, this should be my home, but I now understand that it may legally never happen. I think that's why many fellow foreigners don't invest too much emotionally in this country, because they know that at any time they could be pulled away. For my children, I hope that they can view China as their home. I'm confident China will come up with a policy that will be more open to the world in the coming years.

The attractiveness of the American dream is that it theoretically represents something for the world, that non-Americans could somehow participate in this dream. My wife and I are good examples: a third-generation Chinese American female whose family left Guangdong’s Taishan region, and a third-generation Swedish/Polish mixed male who has little affinity toward his ethnic origins. This is America—a mixture of the world. Whether the model works or not is still uncertain, and there are many myths we believe in the States about how harmoniously we all get along that seem very questionable.

The Chinese dream is still unclear. What does it mean to the world outside China’s borders? If China is going to be a major world power, it will have to resolve how its domestic dreams interact with the outside world’s desire to participate in China’s rise.

8. What advice do you have for young people who struggle with finding their own cultural identity but still want to contribute to a better world?

I hope that when you can set your professional goals, you are not just focusing on financial rewards. I wouldn't be here if I had solely considered the amount of money I could earn. While I admire those who are successful at business, I think that China has gotten to the point where we should start flexing our emotions; we should demonstrate to the world that there is more to China than just business. I believe that China now should be showing more passion and emotions to the world.

Wang Yangming and Zhu Xi, both Neo Confucians, said that knowledge is not enough. Book learning is not enough. It doesn't develop the full person. There's something in a person that goes beyond just memorization. We in China have to go beyond that. If Mengzi is right, then all of us have goodness in our hearts. We have to come up with a way in China to start urging more people to really share that in a very global way. It is difficult to do in the face of constant criticism, but we have to keep trying.

Interviewer: Yanni Li, Emily Zhang

Editor: Yanni Li, Emily Zhang