Complex Identities

The final section of the exhibition, “Complex Identities,” broadens up the scope of the exhibition to reflect on “home” through multicultural identities. The artists’ works deal with the complex realities of being a third culture kid, growing up in a mixed ethnic household, and the impact of encounters with different cultures. We hope that by concluding with this section, viewers will be able to reflect back on their own lived experiences of “home.”

“So I Beat On” (2016, Revised 2020)

Shizheng “JJ” Tie

Johns Hopkins University

Luoyang City, China

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

The tragic ending remark of The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald greatly disappointed me, who had faith in the man who staunchly believed to recover his love with Daisy, diligently transformed from Gatz to Gatsby, and ceaselessly stared toward the green light.

I stubbornly believed this quotation to ruin this book; similarly, I condemned Americanized Chinese foods to ruin my new American life.

Born in Luoyang whose rich heritage cultured my Chinese identity profoundly, thirteen-year-old I left my hometown to America, disappointed by Chinese education which featured mechanically cramming in information, copying it onto exams, and expunging it when they were over for the next round of cramming.

After leaving my family and friends to a foreign land, I lived with an American host family. Endless were sleepless nights imbued by homesickness. Incessant were the apologies for unintentional grammar faux pas. However, my biggest challenge was not language barrier, but confusion and anxiety created by the new things I encountered.

Especially, I loathed Americanized Chinese foods: the syrupy sweet-and-sour sauce enveloping canned vegetables, the texture of chewy yet coarse fried chicken bits sliding down my throat, and the flavorless fortune cookies resembling nothing like exquisite Chinese pastry. I felt insulted by these phony Chinese foods, which sycophantically ditched their characters for American palates.

Resentfully, I longed for the thirteen years I spent in China, fondly surrounded by my family and friends and real Chinese food. Just like fearing the weird-looking entrees smothered in cheese, I feared the myriad people I encounter: their nations have names I couldn’t pronounce; their religions have customs I feared to insult; their cultures have views conflicting with mine. Stemming from this fear, my defensive stubbornness swore never to change.

But then I changed.

I changed as I stopped tenaciously searching for authentic Chinese restaurants to replace my past. Instead, I savored Mediterranean hummus, Texas steak, Japanese sushi, and Thai curry. Ditching my obsession with the “good old days,” I bravely embraced the unknown--whether it be delivery pizza or general American life. I realized that instead of “green light”, a daunting future compromising my past, America is the braided horses at Fulton County Fair, the drive-in movie nights, the yelling coach at track meets, the Nutcracker Ballet show with my friend-teacher whom I deeply appreciate.

So I beat on. My Chinese heritage is no longer a nostalgic wound hurting when I lament over my unfathomable future but a proud reminder of my undefeated spirit and new identities--an unconventional dream-seeker, an epicurean adventurer, and a studious pursuer restlessly staring at the “green light.”

Disliking Fitzgerald’s negativity toward recreating the past, I still dislike Orange Chicken and Chop Suey. However, I can now appreciate The Great Gatsby despite its “borne back ceaselessly into the past” while enjoying chili soup with my rice, because I’m brave enough to relish my future life in a multifaceted new world.

There is no Map 没有地图 (2019)

Angela Wang

Wellesley College

Nashua, NH, US

“The Chinese phrase “没有地图” translates to "There is No Map.” For third culture kids growing up in today’s globalized world, there is no clear map to guide through the cultural growing pains that might be experienced. After a trip to Croatia, I was struck by the minimalist wayfinding signs that were designed with universal icons for all travelers to comprehend. These simple wayfinding arrows appear in my piece as guiding markers for the viewer to indicate how to fold the map back up. Once opening the map, a memory book is revealed to show imagery of temporary homes, such as a hammock as a makeshift bed and a nostalgic kite from my childhood home in Chengdu, China. The map is signed on the back with both my English and Chinese names, reflecting my conflicting identity within two vastly different cultures.”

The Fridge (2017)

Bingcong Zhu

Columbia University

Shanghai, China

*Read the play here.

"The Fridge features a fight between an interracial couple, which begins simply with what should stay in their fridge and what shouldn't, but increasingly touches on their personal habits, and eventually, their perception of home and family. The inspiration for my play came from the household between my Chinese aunt and her Austrian husband. Even though they love each other very much and try their best to respect each other's habits as rational adults are supposed to, their predilections for certain food and drinks, and therefore bias against the other's different preferences, still lead to slight tensions at home every now and then. This makes me wonder if food preference is something so fundamental to our notion of home, that it can hardly be overcome even with our similarly deeply rooted "universal value" about respect and understanding.”

Characters:

Wife - a short, skinny, energetic Chinese woman between 25-35 years old. Had already lived in the US for a while before meeting and marrying her husband. May or may not have an accent. Likes to say "ah" every now and then. Think: Christmas Eve from Avenue Q, but less cynical. Her mom usually lives in China and has minimal exposure to the American culture.

Husband - a slightly chubby Caucasian man between 25-35 years old, with a cherubic, unshaven face. Think: Andy Dwyer from Parks and Recreation, perhaps a little more self-conscious. Loves his wife and his video games.

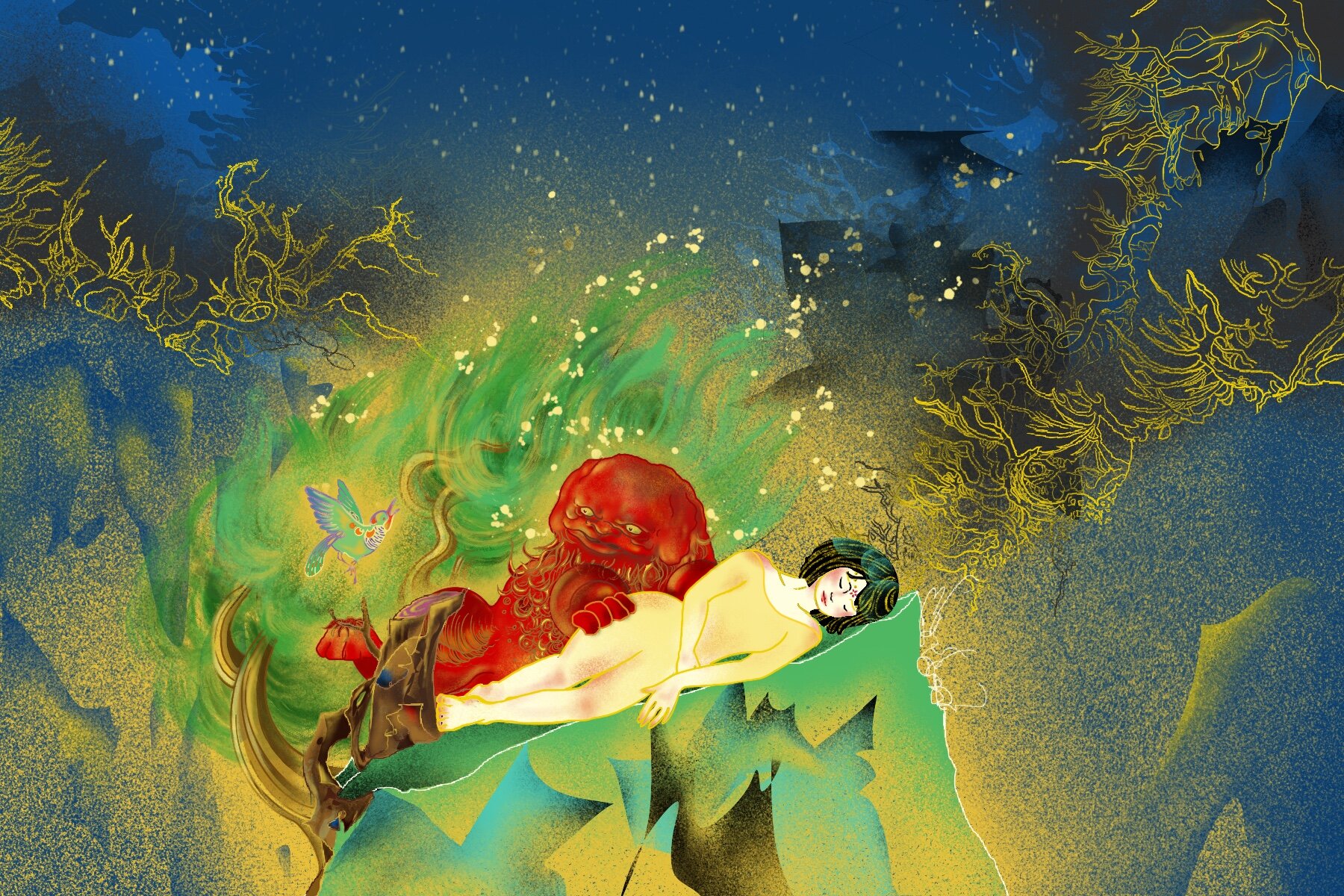

Mountains (2020); Rivers (2020)

Yushan (Nancy) Chu

Wellesley College

Beijing, China

“Landscape is an idea that evokes the most visual and aesthetic connotations in philosophical terms to denote a sense of space and location. At the same time, it represents a genre in traditional Chinese painting that focuses on the painterly depiction of mountains and rivers. I chose the same subjects to express my own sense of home, embodied and encompassed by the physical space of a room in Beijing, where I had only sporadically returned to during school breaks but suddenly had to stay for a long time. After spending two years in college in the US, the home that used to be filled with living experience and memories was replaced in my mind by a “landscape” – something to be looked at, not to live in. However, by representing this “landscape” with my own choices of medium, color, cultural motifs, and composition, I intend to re-establish my emotional connection with the physical place I call home while celebrating the cultural and social dimensions of that living experience. In doing so, I want to resume my agency over deciding my own cultural identity and sense of home.”